!!!DANGER!!!

It is illegal in the state of West Virginia and the National Park Service to enter and or explore abandoned coal mines! They are not natural cave systems! They are a network of man made tunnels reaching miles underground, stretching in many different directions, full of hazards such as blackdamp, (air without breathable oxygen), methane gas, dangerous mine roof conditions and other life threatening hazards. They are extremely dangerous.

John Nuttal and Nuttalburg, Brown and South Nuttal

Of all the abandoned coal sites and communities in the New River Gorge, two, Nuttalburg and Kaymoor, are visited by more tourist every year. Not just in the summer season, but all year round, visitors frequent these two former coal mines. Some of the best and well preserved structures tipple, (coal processing facilities), can be found.

As stated, many visitors frequent the Gorge and these former towns. Sadly, as some video the remains, their "descriptions" leave little to being truthful. Mainly because they simply may not be too familiar with coal mining and terminology as someone who is. No intent to offend anyone with this statement, but our hope with "Heritage Lost, The New River Gorge", is to provide some form of knowledge and history of these places before nature truly does reclaim them. Nature is indeed a master reclaimer and the Gorge is a fantastic place to see this in its beautiful process.

John Nuttall source National Park Service

John Nuttall was born in in 1817, in Accrington England. Having lost his father when he was very young, John and his brothers began working in the coal mines in England at a very young age. Back in those times and up until the early 1900’s, it was not unheard, of young children working alongside their fathers or among adult males in basically any industry. Not at all unfamiliar with hard, brute labor, John was rumored to learn all he could about the industry and dreamed of leaving his native England to seek his fortune in America. He left England in 1849, heading to New York, shortly thereafter, he had saved enough money to bring his young wife and their three children to the United States.

In 1849, his wife Elizabeth died leaving him to raise his four children. Nuttall then headed south to Pennsylvania with his dreams still firmly intact, when he heard rumors of an untouched coal field being opened. With a few highly intelligent business moves, Nuttall then purchased land to open his first coal mine in the area calling the community, Nuttallville.

Something to take into mind about early coal mining places in the United States. Most were in some of the most rural and forsaken areas, usually covering some of the most rugged terrains imaginable. Towns or basically what one would consider as “civilization” were many miles away and usually only accessible by walking or horseback. Roads or what we know as roads were only a dream. Wagons being the only means to actually haul goods in and out of these regions if a railroad was not already in place or at least nearby. During the late 1800's, when the New was being settled, machines that are used today to construct roads were not invented yet. Most roads were created by using hand tools and no doubt, long, arduous days of manual labor.

Coal operators would buy up the surrounding land of a proposed mine site, thus enabling them to legally cut the local forest for timber, milling was usually done on site, providing lumber in which to build structures. Potential coal miners coming into the area seeking employment would certainly need a house to live in. A store from which to buy dry goods and food. Schools for their children, a doctor and basically everything we currently take for granted. It was up to the coal operators to provide this for the miners thus making the little new community self-sufficient and able to provide for a work force. Everything the miner and his family needed to survive was sold in the community. Many miners showed up on payday to simply receive a pay stub, after his weekly purchases and expenses were deducted...a pay stub was all he received.

It is also necessary to mention that, due to the seclusion of these coal towns from the rest of the world, miners were not usually paid in US currency. A form of payment called, “scrip”, was issued as payment. It usually had some form of embossment reflecting the coal company that issued it and only good for use on the said coal company’s property. For example, scrip used to pay a miner with Mr. Nuttall's coal company was not accepted at Mr. Fords coal company store. It was actually worthless, and not accepted by no other place than Mr. Nuttall's mines. Practices such as this was commonplace in all the coal mining towns of West Virginia in the early years of mining. The use of scrip was possibly phased out as the industry started to decline and access to other parts of the state became more prominent in the late 1940’s to 1950’s. Also to be noted, a miners supplies, tools and etc. for the job he was hired to do, was also purchased by him at the company store. The company did not provide tools to work with as they do so today. Loaning truth the the 1955 song by the late Tennessee Earnie Ford, entitled "Sixteen Tons", lyrics reading, "Saint Peter dont-cha call me cause I cant go. I owe my soul to the company store".

Nuttall's mining investments proved to be very lucrative in his new home of Nuttallville, Pennsylvania. His desire to continue to invest in the industry increased when he heard of another unopened, virgin coalfield in the New River Gorge area of southern West Virginia. He had heard rumors of the C&O wanting to brave new territory in the Gorge area by laying track. Hoping to find a shorter and easier way of getting coal to the Ohio steel foundries along the Ohio River. With the proposed railroad going through, it would open up the region for mining and be able to more readily ship coal across the country to buyers. Very lucrative indeed!

At the age of 53, John Nuttall came to the Gorge area to explore. He was one of the first investors to come into the area with hopes and plans of opening coal mines to extract the abundant reserves of the region.

In the fall of 1870, Nuttall was reported to have visited an inn in the area burning a type of coal that produced incredible heat. When ask, the locals told him where the coal had been found and Nuttall found the coal seam directly above the river where the C&O railroad was proposed to go through. History recalls that he then bought up as much land as he could for a then reported $1.00 dollar an acre.

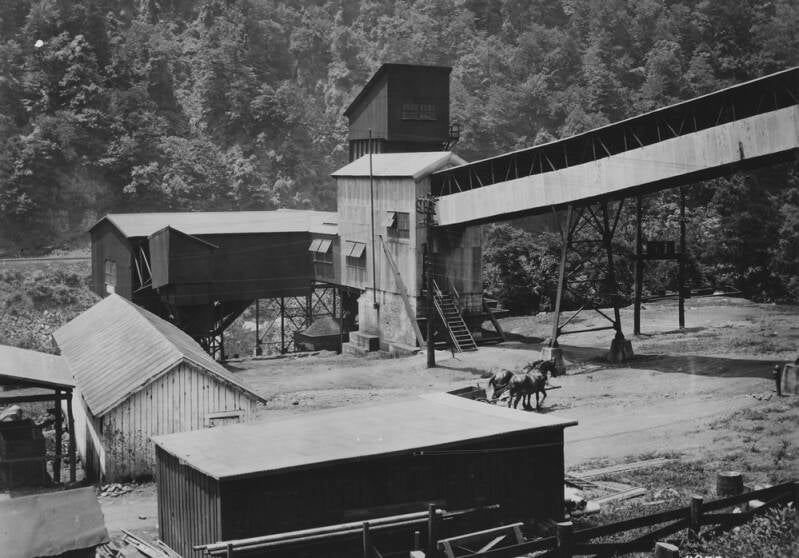

Nuttalburg circa 1926 source National Park Service

He then began to open up a mine in the Sewell seam along the New River Gorge and building a town in which to host and provide for the miners he would need to work the seam. He named his new venture, “Nuttallburg”. He had actually began mining coal in his new mine long before the C&O had completed laying their new track along the New River Gorge. Once the railroad was completed, Nuttall was ready to ship his product to eager buyers across the country.

By 1893, the town of Nuttallburg boasted of having almost 300 residents. The town had a doctor, a company store and schools. Unfortunately during this period, segregation was still a way of society and both schools and churches were built to accomidate both black and white miners. As immigrants flooded into the area seeking emloyment, the communities grew to meet their individual, religious needs as well. John Nuttall operated the Nuttallburg mine very successfully and prosperously until his death in 1897. The town and mine continued to remain operated by his family, including his son-in-law.

By 1919, the Nuttall family feared the mine had about reached its full potential and was close to mining out. Mining methods and the means of actually getting the coal from the mining face, or area inside the mine that coal is actually being mine, to the surface was limited. During the time period the Nuttall mine was first operated, mining usually took place by means of under cuting the coal seam with picks and drilling holes in the coal face to place dynamite into, thus blowing the coal loose from the seam.

Coal was then hand loaded by miners with shovels, into small coal cars, then pulled to the outside by means of mule or pony teams. The deeper the mine became, the harder and more difficult it was to get the coal to the surface until the invention of electric or battery operated mine locomotives or conveyor belts. Animals would not last very long pulling hundreds of tons of coal long distances and, in fact, each mule or horse would cost the company money to replace.

It has been noted in many documentaries and books that coal operators cared more about their livestock than they did about the human workforce. This is indeed a truthful statement and not a fabricated one. Miners were, in essence, a dime a dozen. They worked for the company. Got paid in company scrip. Used tools sold to them by the company.

Lived in company owned houses they had to pay the company rent for. Shopped only at the store provided by the company. Basically, the company owned them and it was virtually impossible to save for a more promising future.

Mining conditions were horrible to say the least. Few if, any safety laws were in effect and safety inspections by state and federal agencies didn’t exist. It was honestly up to the coal company if they integrated safety into the workplace or not. Men lost their lives on a daily basis and in the eyes of so many coal companies, it was no big deal. If one man died today, there was possibly another worker outside wanting to take his place. If a man died in a fatal accident underground or was sick and couldn’t work, he and his family were evicted from their company house by mine security guards. Labor was cheap and easy to come by. Mules and horses were a commodity the company had to purchase in order to get the coal to the surface and the company didn’t like spending money. Therefore, it is a true statement that the company cared more about losing an animal than they did a coal miner.

Nuttalburg Tipple, circa 1926 source National Park Service Present day Nuttalburg Tipple source author

The New River Gorge once was comprised of over 60, small coal mining towns along the river banks. These small, self contained communities stretch, not only along the banks of the river itself, but extended up each hollow. Wherever a mineable coal seam was found, it would appear a community would start to be built to suit the needs of the miners and the company that sought to take the mineral from the earth. Each with its own laws and rules. Each with its own form of payment that was non-negotiable with other coal towns along the Gorge.

From Glade Creek to the town of Ansted, towns sprang up seemingly over night. Coal mine operations were going in at a wild rate. complete with processing facilities then call “tipples”. Beehive ovens were contructed to process the raw coal into a more substance called , “coke”, which is used in the processing and smelting of steel.

The New River Gorge still is dotted with these coke oven remains. Now nature has about fully reclaimed what man once blatantly destroyed. Early photos of the region compared to current photos would surprise anyone who tried to view them side by side in a comparison. Today, the landscape of the New River Gorge is beautiful. Deep, lush, green forest cover the area and is indeed a natural beauty to see. But during the era of the coal industry, the hillsides were cut clear of trees in order to use as building material in the construction of tipples and towns.

Bank of coke ovens in todays Nuttallburg. Present day Nuttallburg beehive coke oven

Remnants of the community of Seldom Seen Source National Park Service

The earlier photo of the Nuttallburg tipple in the early 1900’s details the mountainside basically void of a hardwood forest. Today, the land has recovered and the forest has once again regrown to almost being difficult to look up the hill towards where the original mine entrance was located. Hiking trails dot the landscape providing some very beautiful scenery. So hard to imagine the area when mining was being done and especially the coke ovens in full operation. Not many are aware of two other adjacent communities associated with Nuttallburg. Down river of the bank of coke ovens, a trail leads to the remains of the community honestly called, "Seldom Seen". (refer to above photo, courtesy of the National Park Service). The other community was located at the upper end of Nuttalburg. Across from the river on the opposite side of Nuttallburg called, "South Nuttall". Also noteworthy is the fact that Nuttallburg was actually served by two railroads. The mainline being the C&O line that ran alongside the New River and the second was a narrow gauge railroad operated by the Keeney Creek Railroad. It ran up Keeney Creek and served coal companies that were located along Keeneys Creek up to Lookout, Winona and Dupree. The line ran down Keeneys Creek, underneath the button and rope conveyor belt of Nuttalburg, into a switchback and then down to the river at Nuttallburg.